Kraków 2015-11-25

Military forces of the Moscow state in Poland. 1944-1994.

Entry.

This article is subjective and serves only to signal a "problem" that existed in Poland for 50 years, and is now at least passed over in silence and considered non-existent. No publication on this subject has been published so far. The Moscow State Occupation Army (CCCP) was the problem. So – "Kurica not bird. Poland not abroad.”

The history of the Polish nation is rich and beautiful, and living between two aggressive nations, we had to show courage and bravery many times while defending our sovereignty. Especially the 20th century showed the exceptional animalism of Muscovites and Germans. In 1918, after 123 years of partitions, Poland regained its sovereignty and within twenty years, from an agricultural country, it became an agro-industrial one. But our fathers were not allowed to build prosperity peacefully, because the brothers reunited and together they destroyed Poland in September 1939. After World War II, Poland became a vassal state of Moscow, with the consent of the world’s greats. However, the Muscovites realized that they were not strong enough to turn Poland into another republic of the Soviet empire. They conquered Poland with the appearance of sovereignty. Such a pseudo-sovereign Poland was convenient for them. It was as if they had an overseas colony whose riches they enjoyed without restriction.

It must be remembered that all the borders of today’s Poland were predetermined by world powers. Mainly via Moscow, London and Washington. Winston Churchill, who needed Stalin to win over Germania, ultimately did not agree to the creation of a third front in the Balkans. The Germans, when they began to lose, hoped to leave the borders of 1939. However, Stalin seized the opportunity to enlarge his colonies. He continued what he personally failed with the armies of the illiterate Budyonny and Tukhachevsky in 1920.

In 1945, Wrocław was not captured by Muscovites. It was Wrocław that was to be the main seat of the Moscow authorities in Eastern Europe. However, Wrocław was so damaged that Legnica became Little Moscow, which did not suffer so much during the war. Legnica, a very beautiful city, which was turned into ruin by Muscovites, but already in peacetime. To this list we must add Szczecin, about which in 1946 it was not known whether it would be in Poland or in a new creation, which in 1949, the state of the GDR became.

In this way we came to the so-called Regained Territories. It is true that historically these areas were inhabited by Slavs. However, they have been Germanized for many centuries. In 1945, they were incorporated into Poland. The later temporary nature of this area is evidenced by the attitude of the recent communist president of the Republic of Poland, Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who vetoed the act of universal enfranchisement. This enabled the Germans to regain private property in the so-called Recovered Territories, and the Poles who had settled there for 50 years were thrown out. And there was no need to change the borders. The much-vaunted solidarity in the European Union was and is a sham. This solidarity lies at the bottom of the Baltic Sea in the form of gas pipelines connecting the two brothers; Muscovites and Germans. But let’s get back to the topic.

Moscow state army in Poland.

The troops of the Moscow State (CCCP) in the amount of about 500,000 soldiers entered Poland as the 2nd Belorussian Front in 1944, and remained here. In August 1945, in Potsdam, the borders of communist Poland were proclaimed. The maintenance of the CCCP troops in the Polish People’s Republic fell to the Polish nation.

After the end of hostilities, in May 1945, by the decision of the dictator Stalin, four groups of troops were organized in the countries subordinated to the Moscow state. These were: the Group of Occupation Forces in the GDR, the Central Group of Forces in Hungary, Austria (the end of the occupation in 1955) and Czechoslovakia, the Southern Group of Forces in Romania and Bulgaria, and the Northern Group of Forces in Poland.

The Northern Group of Forces of the Soviet Army in Poland was most often referred to as PGW or PGW AR. Their military units were mainly deployed in the so-called Recovered Territories. It was the Soviets who decided which objects they would occupy and what they would put in them. The maintenance of these troops fell on the shoulders of the Polish nation. In this way, the Muscovites achieved what they started in 1920, but then they failed before Warsaw and fled from the Polish Army and the Blessed Virgin.

It is not known how many soldiers of the Muscovite state were in Poland. It is estimated that by 1950, it was about 300,000 – 400,000. When the international situation inflamed at the turn of the 40s and 50s, this number dropped to about 80,000 soldiers. What happened to them? Certainly they were not demobilized, because at that time the number of soldiers in the GDR increased. In 1992, General Dubynin stated that 500,000 soldiers leaving East Germany must pass through Poland. In 1950, the war in Korea was going on, so the Muscovites transferred some of their forces to the Far East. From 1950 to 1990, the number of soldiers in Poland ranged from 50,000 to 80,000 and fluctuated. This oscillation was inspired by international events, such as the deployment of troops to Cuba in 1961 and Afghanistan in 1980.

The answer to the question sounds interesting; Why did Moscow keep such large forces in Poland? There were two reasons. The first was the psychological support of the communist authorities installed in Poland by force. "What are we?" There was also a lack of trust in the local communists. Secondly – "We have already gained a long way to the Atlantic Ocean and how can we go further bringing peace and equality."

The possession of the Soviets in Poland.

In 1945, the Soviet army had nearly 100 garrisons in Poland, which were self-supplying, i.e. they took contingents from the area. The number of these garrisons gradually decreased, but there were over 60 of them all the time in the Polish People’s Republic (65 is most often mentioned); Bagicz, Białogard, Borne Sulinowo, Brochocin, Brzeg, Brzeźnica, Bukowiec, Burzykowo (Stargard Szczeciński), Chocianów, Chojna, Czarna Tarnowska, Czeremcha, Dębica, Duninów, Jankowa Żagańska, Sycamore, Karczmarka, Kęszyca, Kluczewo, Krzywa, Kutno, Lądek Zdrój, Legnica, Lubin, Lubliniec, Łowicz, Miłogostowice, Nadarzyce, Namysłów, Nowa Sól, Nowosolna, Oława, Podborsko, Poznań, Przemków, Raszówka, Rembertów (Warsaw), Rudawica, Siedlce, Słotnica (Stargard Szczeciński), Sokołów, Strachów/ Pstrzą, Strzegom, Sypniewo (Gródek), Szczecin, Szczecinek, Szprotawa, Śniatowo, Świdnica, Świętoszów, Świnoujście, Templewo, Toruń, Trzebień, Wilkocin, Wólka Kałuska, Wrocław, Wędrzyn, Września, Wschowa, Zbąszynek, Zimna Woda, Żagań.

At the end of the 80s, Muscovites were officially stationed in 59 garrisons. They had at their disposal 13 airports, 6 (4) training grounds with an area of 50,000 – 60,000 hectares, a naval base in Szczecin and slightly counting nearly 10,000 facilities. The Soviet army used a total of 70,000 hectares of various lands. They had 1,200 apartment blocks with 10,000 apartments. They occupied 240 single-family houses and villas. They had 2,500 barracks (including 2,150 from before World War II, and 350 built in the times of the Polish People’s Republic). The Soviets had 800 warehouses.

Units stationed in Poland were first-line units. Some publications used the terms "excellent". Such slogans were used to boost the morale of the semi-illiterate. PGW had 600 tanks and 300 combat aircraft. At the time of the attack on Western Europe, units from East Germany would move first, followed by units from Poland. The Polish People’s Army was to move to Denmark.

Real, new Soviet cities began to be created in Poland in the 1970s. At that time, large closed housing estates with several or more than a dozen high-rise blocks were built. They had full infrastructure with: central boiler house, water intake, shops, schools, sports facilities and others. Only officers and their families lived there. Conscript soldiers lived only in the barracks.

All strategic military objects on the maps of Poland were blank spots or forest areas. Only in 1989, maps appeared where these areas were marked as a "closed area". They were surrounded by at least a double fence of concrete posts and barbed wire. Mushroom pickers could come across such fences and warning boards in Polish – "Military area, no entry". Less often written in Cyrillic. There were electric fences, but in the second zone of the fences.

Main military bases.

Undoubtedly, the most important city for Muscovites was Legnica, where they occupied 1/3 of the city. First of all, in the so-called Square. The city of Legnica received the unofficial name of Little Moscow. The most important locations were also Świętoszów, Świdnica, Szczecin and Borne Sulinowo. The most important air bases include: Bagicz, Chojna, Brzeg, Kluczewo, Krzywa, Szprotawa. Airports are described in separate chapters.

Operational commanders of PGW AR.

June 1945 – October 1949: march. Konstantin Konstantinovich Rokossovsky, then stayed in Poland as a super commander. October 1949 – August 1950: Col. Gen. Kuzma Petrovich Trubnikov. September 1950 – July 1952: Lt. Gen. Alexei Ivanovich Radzievsky. July 1952 – June 1955: Lt. Gen. Mikhail Petrovich Konstantinov. June 1955 – February 1958: army general Kuzma Nikitowicz Galicki. February 1958 – March 1963: Colonel General Georgy Ivanovich Chetagurov. March 1963 – June 1964: Col. Gen. Sergei Stepanovich Mariachin. June 1964 – October 1964: Lt. Gen. Alexander Pavlovich Rudakov. October 1964 – June 1967: Col. Gen. Gleb Vladimirovich Baklanov. June 1967 – November 1968: Army General Ivan Nikolayevich Shkadov. December 1968 – May 1973: Col. Gen. Magamied T. Tankaev. June 1973 – July 1975: Colonel General Ivan Alexandrovich Gerasimov. July 1975 – January 1978: Col. Gen. Oleg F. Kuliszew. February 1978 – August 1984: Col. Gen. Yuri Fedorovich Zarudin. August 1984 – February 1987: Col. Gen. Aleksandr Vasilievich Kovtunov. February 1987 – June 1989: Colonel General Ivan Ivanovich Korbutov. July 1989 – June 1992: Col. Gen. Viktor Petrovich Dubynin. June 1992 – September 1993: Colonel General Leonid Illarionowicz Kovalev.

Legal grounds for stationing Muscovites in Poland.

Initially, there was no agreement sanctioning the presence of the Soviets in Poland. According to international law, it was a typical occupation. The situation changed in 1956, but the beginnings of this change must be sought in 1955. It was then that the NRF was admitted to the NATO pact and their armament began. Moscow was looking for an antidote and came up with the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, which was signed on May 14, 1955 in Warsaw and later called the Warsaw Pact. This arrangement partially sanctioned the stationing of the army of the Muscovite state in Poland.

But the Polish nation was about to feed the occupiers, who committed numerous common crimes, which will be discussed below. This was especially true of the cities where they were stationed. They demanded the return of properties seized by the occupiers, such as in Legnica. For the years of deep communism, these voices were very courageous and often came from members of the Polish United Workers’ Party. In official letters to the PZPR authorities, open questions were asked about the sense of Muscovites staying in Poland. Who bears the costs? The Poznań Uprising in June 1956 added courage.

In October 1956, the Polish communists convened the 8th Plenum of the Polish United Workers’ Party. A plenum is a council of the main and decisive political force at that time. But no one from Moscow was invited to this plenum. The Muscovites realized that there could be rebellion and revolt in Poland. In order not to let the situation get out of control, they sent tanks towards Warsaw. From Pomerania, from Borne Sulinowo, the Soviet armored units went through Września and Włocławek, from Lower Silesia, from the region of Żagań and Bolesławiec, they went through Łęczyca and Łask towards Łódź. The warships of the Soviet fleet entered the Gulf of Gdańsk at that time. On all Polish borders; in East Germany, Czechoslovakia and the Republic of Belarus, a state of increased combat readiness was announced. This caused even greater reluctance of the Polish nation and the Polish Army to their presence. At that time, the Polish Army was subordinated to the Ministry of National Defense, headed by a Muscovite. He ordered the Polish Army to stay in the barracks. But the military units of the KBW and MO were not subordinated to him and remained loyal to the Polish United Workers’ Party. A small but significant difference. On October 19, 1956, Soviet tanks stopped in the area of Łódź, Włocławek, Łowicz and Sochaczew. On that day, the PZPR plenum was held. At 07:00, Nikita Khrushchev arrived in Warsaw, accompanied by Molotov, Kaganowicz, Mikoyan and Marshal Konev. The PZPR wanted the delegation to arrive a day or two later. Muscovites, however, wanted to influence events. Chess was played for two days. The PZPR finally confirmed loyalty to Moscow and the development of communist Poland. There were staff changes in the authorities of the Polish United Workers’ Party. The tanks returned to their bases.

On December 17, 1956, an agreement was signed between the government of the Polish People’s Republic and the CCCP government on the legal status of the Soviet troops temporarily stationed in Poland. Back then, "temporarily" meant forever. According to this agreement, the total number of Soviet troops in Poland was set at 62,000 – 66,000 soldiers, including land forces – 40,000, air force – 17,000 and navy – 7,000. Poland. The problem was that there was no way to verify that the Soviets had kept this agreement and the role of this plenipotentiary was limited to fulfilling the wishes of the Moscow side. The plenipotentiary did not know how many soldiers were stationed and what equipment they had. After all, it was a secret.

At this point, it is worth mentioning other military movements of the Soviet army in Poland. Interestingly, in 1968, tanks from Soviet bases in the People’s Republic of Poland did not move. Tanks of the Polish People’s Army went to Czechoslovakia. Poland was also a transit point for Soviet forces from the Kaliningrad region to Czechoslovakia. A different type of activity by the Soviet troops was observed from the late 1980s to early 1982. These movements were related to the rise of Solidarity and martial law. Soviet tanks did not leave the barracks, but the armed forces secured communication routes and expanded the communication system, including satellite communication. Commando units in Legnica and Borne Sulinów were ready to fly to Warsaw to secure the "appropriate" activities of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party.

Behavior of the Soviets in Poland.

The Soviet soldier staying in Poland evolved along with the changing environment and the passage of time. 50 years is a very long time. Initially, they were illiterate and semi-illiterate. Often criminals. With little knowledge of technology. They couldn’t handle central heating, water and sewage systems. When the toilet was clogged, they dug holes through all the floors of the building to the very basement. They had zero knowledge of culture and art. Books served as kindling. In the rooms of the tenement houses and villas they occupied, they lit fires in the middle of the living rooms. They spent their free time drinking alcohol and raping women they met. The age of the victims did not matter. Robberies and thefts were the order of the day. Polish law enforcement agencies and courts had no influence on them. Road accidents were relatively frequent. Farmers reported frequent crop losses. This situation even threatened the escape of new Polish settlers from the regained lands. They really behaved like in a conquered country.

Over time, the number of people with a decent education increased. In 1958, the CCCP introduced the obligation to complete a 9-year, and at the beginning of the 70s, a 10-year elementary school. However, not all children completed it. From the 7th grade, it was possible to send them to learn a working profession. The elementary school was theoretically the equivalent of elementary school, but in fact its full completion gave a secondary education enabling the continuation of education in higher schools, called institutes in the state of Moscow. Let us remember that the CCCP was a police-military state, and all military and militia schools had the status of universities. Thanks to this, there was no shortage of new cadres for the army and militia. The effect was that men went to the army and women went to factories and, for example, welded fuel tanks for airplanes.

Naturally, there was no shortage of officers willing to go on missions. They treated their stay in Poland as a distinction and an opportunity to learn about another culture. They were already able to appreciate the building and architecture culture of the previous Germanic generations. Maybe they didn’t know about it, but they didn’t mindlessly destroy it anymore. Their earnings were very high. A Soviet officer earned two or three times more than an officer in the Polish Army. Just like in the Polish Army, they were entitled to a business apartment and the right to bring their family. Officers had the right to wear civilian clothes off-duty. Conscript soldiers did not have such a privilege. The conscript soldier’s salary was only $2-3 a month, with which they had to buy cleaning products and cigarettes. Therefore, thefts were frequent. For comparison, the Polish Soldier (private) received a salary of about PLN 170 per month (1982) plus all cleaning products and cigarettes.

A Soviet conscript soldier went on foreign missions only once and they always remembered it very well. They often compared this period to "wonderful moments". Professional soldiers went on missions several times, if only they did not get into trouble. They don’t want to talk about their trips. Why? There are several reasons. Usually not wanting to spoil the reputation of their children and grandchildren, who still go on missions, although not to Poland.

However, among the soldiers of the conscript service, culture was still poor. The 1960s saw new requirements for applicants to go abroad; citizenship of the CCCP, at least secondary education, no criminal record (which also concerned their family members, for example father or grandfather), appropriate moral and ideological values and "adequate health" for the service performed. Similar requirements then appeared in Poland for our soldiers leaving for UN missions. In the CCCP, these requirements were not always met. This was due to the shortage of some specialists. This was particularly evident among drivers of military vehicles. Even criminals were taken here.

Soviet soldiers used PKP railway crossings free of charge. You could often meet them at Polish railway stations. They were always in groups, never alone. They are legally dressed in their green and yellow uniforms with forage caps on their heads. Often with a long gun, usually a kbk AK carbine, but no ammunition. The Polish WSW (Military Internal Services) steered clear of them and vice versa. He had his internal services. They often had separate compartments in the cars, bearing railway information in the form of a standard RESERVATION print stuck on the glass of the compartment door. The conductors didn’t even look there.

Much more often, Soviet soldiers traveled in their own trucks. Almost normally it was a column, consisting of several trucks. They never refueled at CPN (Centrala Produktów Naftowych) stations. Each vehicle had a fuel supply for a distance of 600 km. The vehicle was driven by a driver, but responsible for the convoy and security was the escort officer, sitting in the first vehicle next to the driver. They stopped at village shops or taverns for rest stops. They usually bought alcohol in corked and sealed bottles. They uncorked it and drank it down. Sometimes they bought bread and pickled cucumbers for a snack. Sometimes cigarettes and matches. If they bought a newspaper, it meant that they had a physiological need and would use the newspaper in the nearest forest.

From the beginning of the 1960s, the development of trade between the Soviets and the local population dates back to the beginning of the 1960s. The permanent crisis in the Polish People’s Republic favored such an exchange. Fuel was the primary commodity, but everyday items were important; soap, toothpaste. After gaining trust, trade relations deepened. Muscovites brought gold jewellery, watches, toys (especially battery-powered ones), and even spare parts for Lada and Volga cars. The more resourceful Muscovites, before returning home, sold what they could from military equipment. At the beginning of the 1990s, they even sold bayonets, short and long guns, and ammunition. If there was a buyer, they would even sell a tank and an airplane. And if the matter came to light, they would deny that they had lost anything.

Both the Soviets and Poles did not tolerate Ruthenian relationships with a Polish woman, but for different reasons. Few cases of love between a Polish woman and a Soviet soldier ended with the girl receiving CCCP citizenship and sending both to another garrison, in another part of the world. The Polish nation did not tolerate such relationships because of the always negative attitude towards the occupiers.

Talks about the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Poland.

Social and economic changes in Poland in 1989 resulted in serious talks on the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Poland. At the outset, we must write that President Lech Wałęsa wanted to gird himself with all the glory for the positive settlement of this matter. But the truth is that it was he who wanted the creation of Soviet-Polish companies in the former Soviet bases and he blocked the disclosure and liquidation of the Soviet spy network in Poland. The real director of removing the soldiers of the Moscow state from Poland was Prime Minister Jan Olszewski, who paid for his opposition to Lech Wałęsa and the post-communists by dismissing the government. We will emphasize once again – Prime Minister Jan Olszewski led to the removal of Soviet troops from Poland.

The Muscovites agreed to leave the bases in Poland, but demanded the establishment of Ruthenian-Polish enterprises (companies) of an extraterritorial nature on their territory. President Lech Wałęsa agreed to this, as he took care of his "left leg" due to his links with the agents. Fortunately, that didn’t happen. The resolution of Jan Olszewski’s government rejected this proposal and it was adopted unanimously. There was a direct clash between the Prime Minister and the President. Prime Minister Jan Olszewski opposed signing a clause to the Polish-Russian treaty on friendship and good neighborly cooperation. As a result, the government of Prime Minister Jan Olszewski was dismissed during a night session of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland. History remembers it as "Night Shift". As a result, the communists returned to power: Aleksander Kwaśniewski, Józef Oleksy, Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz and others. This set the Republic of Poland back a few years. The protocol regulating relations between Poland and Russia, i.e. the Treaty on Friendly and Neighborly Cooperation of May 22, 1992, signed by Presidents Lech Wałęsa and Boris Yeltsin, did not include consent to transform Soviet military bases in Poland into joint venture companies.

Difficult talks on the withdrawal of Moscow’s troops from Poland were initiated on the initiative of the Polish side in December 1990. Subsequent rounds of talks were held alternately in Warsaw and Moscow. Officially, there were fifteen, and there were also hundreds of unofficial conversations. The Polish side proposed that the Muscovites leave Poland by December 1991, i.e. in less than one year. The Muscovites firmly insisted that this would happen by July 1994 at the earliest. They associated it with the need to leave the territories of the former East Germany by the 600,000th army, where the decisions had already been made. The Germans were assured of withdrawal by the end of 1994. The Polish side claimed that since the evacuation of 600,000 will take four years, up to 10 times smaller forces are able to leave within a year. The talks continued.

The Soviets made demands. They demanded financial gratification for the property left behind: buildings and other infrastructure. Poland demanded compensation, especially for environmental damage, which is discussed below. They were also blackmailed by refusing to let soldiers withdrawing from the former East Germany. Then, in January 1991, in Moscow, General Wiktor Dubynin made a statement: The invincible and proud Soviet army, which once defeated the Germans, will leave Poland when it sees fit, along roads and routes it sees fit, with unfurled banners, in a way that it determines itself, and if someone interferes with it – it does not take responsibility for the safety of the Polish population.

In the end, however, a satisfactory compromise was reached. The agreement was signed in May 1992. In the document, the Muscovites agreed to withdraw combat units by November 1992. The rest of the auxiliary units were to withdraw by the end of 1993. In the financial and property settlements, the so-called "zero option".

Degradation of the natural environment.

One of the elements of the talks were visits to the bases in terms of environmental protection.

The degradation of the environment made by Muscovites was large. The area around the airports was severely affected. Gasoline or diesel fuel for cars could be secretly sold to Poles, but aviation fuel (kerosene) was not. There was no demand for them, so they were poured into the ground (into the ground). Why was it poured? Each regiment was to make a certain number of flights. Not all of them were done for various reasons. The papers had to match. So it said it was done. But there was fuel left, so surpluses that shouldn’t have been there. It was poured out. Oils and battery electrolyte were also poured out, not to mention faeces. No Soviet unit had a sewage treatment plant. Even before the start of talks on the withdrawal of hangovers from Poland, in August 1990, inspections began at the interstate level of bases in the then Szczecin Voivodeship. Inspectors of the Department of Environmental Protection of the Voivodeship Office were admitted to the Soviet garrisons in: Chojna, Świnoujście, Szczecin and Kluczewo. Following these inspections, unofficial but alarming articles about environmental degradation appeared in the press. Both in the bases themselves and in the adjacent areas, especially in rivers and lakes. It was described that none of the bases had any sewage treatment plant. The contamination came mainly from petroleum-derived substances. In Kluczewo, it was especially dangerous, because the sewage was discharged into the Gowienica River, which is a tributary of Lake Miedwie, which in turn, since 1976, has been a drinking water intake for Szczecin. Already after leaving the bases, the local residents proved that it was enough to dig a hole, which after a while was filled with a liquid with good combustion properties, and often suitable as fuel for internal combustion engines. In turn, the technical condition of deep wells indicated the possibility of contamination of water veins with petroleum substances. No solid waste was collected from the bases. Most of them were burned in boiler houses. Even plastic packaging, which emits carcinogens into the atmosphere when burned. Subsequent inspections, after the departure of the soldiers, confirmed the same condition in the other bases.

From February 1991, the Muscovites allowed inspections of their bases for the purpose of making an inventory of real estate. This was necessary due to possible discrepancies and mutual accusations.

The original draft of the international agreement, signed by both sides, allowed foreign troops to complete the evacuation by the end of 1993. However, President Lech Wałęsa wanted their departure to coincide with the anniversary of the Soviet attack on Poland, i.e. September 17, 1993.

Departure of the Soviets from Poland.

The first units set off east on April 8, 1991. An echelon with equipment and soldiers of the operational and tactical rocket brigade stationed there left the garrison in Borne-Sulinów. Talks about their withdrawal were still underway. At that time, PGW AR had 53,000 (56,000) soldiers, 7,500 civilian employees and 40,000 members of their families.

Then, more railway transports left from the next garrisons. In their depots there were warehouse supplies and equipment of auxiliary units. Contrary to assurances, combat units were the last to be withdrawn.

The condition of the objects left by the army of the Muscovite state was deplorable. But about it is written below.

On September 17, 1993, on the anniversary of the Soviet aggression against the Republic of Poland, the commander of the PGW, General Leonid Kovalev, reported to President Lech Wałęsa about the completion of the withdrawal of soldiers from Poland. He didn’t report leaving the agency. On September 18, 1993, the last soldiers of the Moscow state left Warsaw’s Eastern Railway Station to the east. In the last group there were 19 officers and 5 generals. According to official information, only a military mission of about 30 soldiers remained in Poland, which later supervised the transit of Soviet troops from Germany to the east. In fact, about 7,000 soldiers remained to secure the passage of East German troops to the east.But the Polish nation knew that all the agents remained, which Messrs. Milczanowski and Mr. Macierewicz wanted to liquidate. Lech Wałęsa did not agree to this. Mr. Macierewicz was the greatest enemy for the political system from Magdalenka and the "Round Table".

Capturing objects.

Taking over the facilities from the Soviet army in Poland was carried out on the basis of an agreement of December 17, 1956, and then by order No. 13 of the Prime Minister of March 25, 1991, and other his guidelines.

During the official transfer of the bases, sapper and chemical units entered the area in search of any unexploded ordnance or chemical substances left behind. The action of removing petroleum substances lasted for nearly 10 years and was carried out mainly by specialized companies at the expense of the Polish taxpayer. On average, 1,000 – 1,500 m3 of highly contaminated groundwater was extracted from one air base.

The condition of the objects left by the army of the Moscow state was very bad. Most of the facilities the Polish Army did not want to take over, because it was associated with additional funds that were not available. Generally, the facilities were placed under the jurisdiction of the communes and poviats where they were located. Local governments had to deal with this problem as efficiently as possible. But it turned out to be very difficult. The management of this property was subject to corruption, underestimation or overestimation of the value of property, and as a consequence, criminal cases. The local scrap metal dealers dealt with some of the property faster. Every metal that could be extracted was "used" by them. Including doors to shelter-hangars and electrical wires.

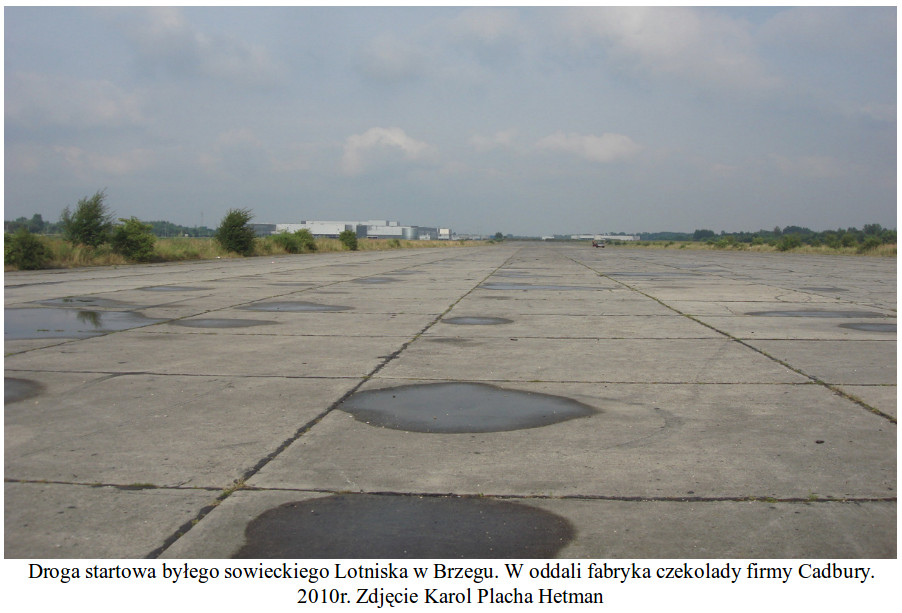

No post-Soviet airport was taken over by the Polish Army. However, there were cases where a part of the area together with part of the RWY was leased by entities interested in small aviation. This was the case in Bagicz and Brzeg, for example. Local governments have developed the post-airport areas in various ways. Generally, forest areas were under the management of the state forests of a given forest district. Large areas of the ascent field have been turned over to agriculture. This was the case, for example, in Kluczewo. The development of buildings was worse. There were cases of taking over shelter-hangars by various economic entities as warehouses. Although not all goods could be stored here due to humidity and low temperatures. Classic hangars were often taken over for various economic activities or religious associations, such as in Brzeg.

Nevertheless, in the territory of the Republic of Poland there are many remains of the soldiers of the Moscow state and they are the goal of many compatriots’ expeditions, especially during the holidays.

Written by Karol Placha Hetman