2023 year

Written by Marek Kaiper

Microwave protection and occupational health and safety at work at radar stations in the years 1970 -1998.

Due to the spread of many radar devices in the Polish Army, protection was introduced for soldiers working in the microwave range (X, S, L bands). As part of this protection, the personnel of radar stations were sent every 4 years for mandatory specialist examinations in designated hospitals. In the air forces, these were initially the Military Institute of Aviation Medicine in Warsaw, the Military Aviation Hospital in Dęblin and the Navy hospital in Oliwa, and later also other hospitals. Initially, the examination lasted 4 days and was detailed, later shortened to 1 day. The test results were initially entered into the "Health Book of a Professional Soldier" and, from 1968, also into a special "Health Book of an Employee employed within microwave range". These books were published by the Headquarters of the Health Service of the Ministry of National Defense. The results of examinations of soldiers of conscript service were entered or stamped in the "Health Booklet of a soldier of conscript service" in the section of the decision of W.K.L. a stamp, e.g. "Capable of working with radar equipment."

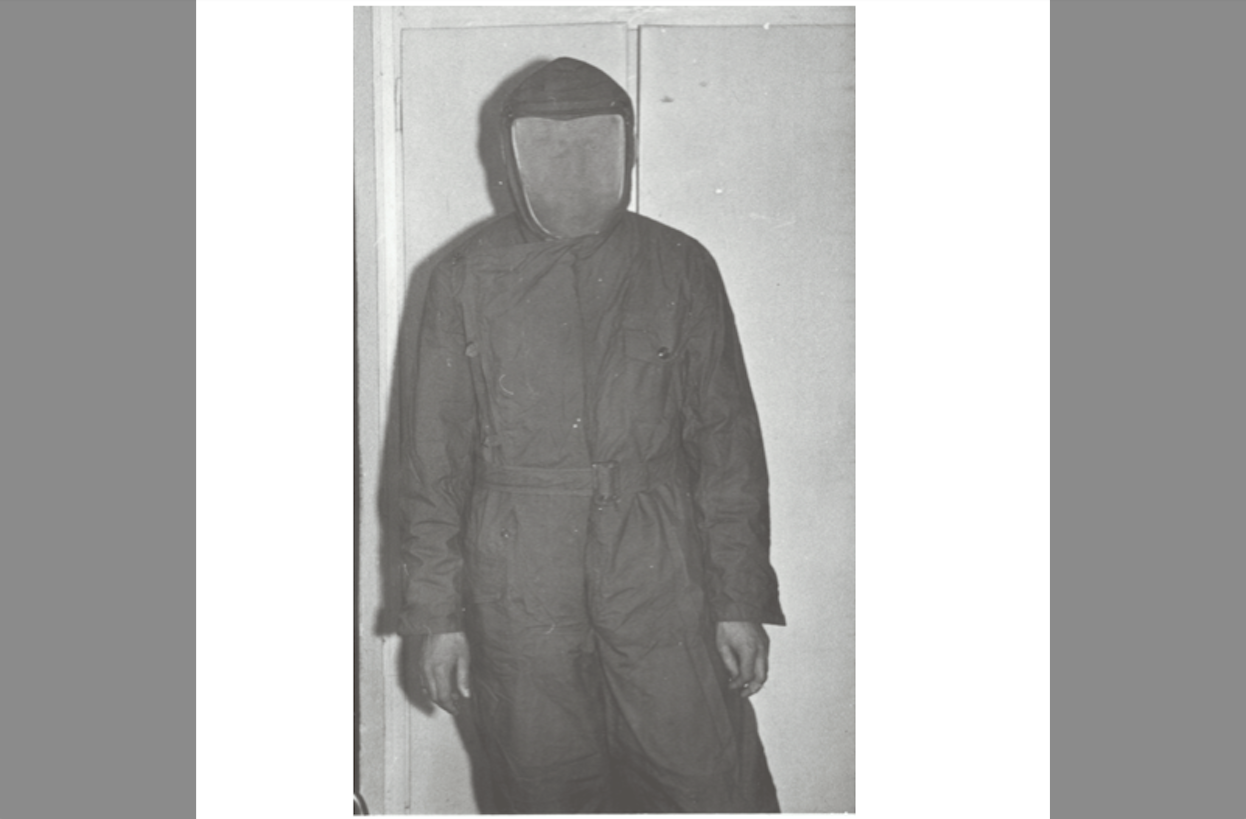

At the end of the 1960s, the personnel of radar stations were also issued with microwave protective clothing designed to protect against electromagnetic radiation in the range of 0.1 MHz – 300 GHz. OM-1 protective suits, OM-2 protective coats and, later, protective glasses. They looked like welding glasses, had round tinted mirror lenses (semi-transparent mirror) placed in a gray flexible metalized cover that fit tightly to the face. If I remember correctly, they were called OM-3, they were very expensive and returnable. The OM-1 suit was equipped with a removable, deep hood with a dense metal mesh at the front covering the face, and ear holes on both sides also covered with metal mesh. This hood had a stiff insert inside, which was used to properly position it on the head. The suit was made of three layers of material: an olive outer layer and a middle and inner layer. An actual protective layer of metallized material was placed between the inner and outer layers. The suit was fastened with a hidden zipper, and the flap covering it was fastened with buttons, and was additionally equipped with a canvas belt with a plastic buckle. There was a pocket sewn on the upper left front part of the suit, the second pocket was sewn on the right side at waist level. Both pockets had flaps fastened with a button. The cuffs of the sleeves and legs were fastened with zippers and additionally secured against unfastening with flaps fastened with buttons.

These suits were rarely used by the staff, personally, during my 21 years of work at the radar station, I used them only twice, including once during exercises in winter, when it was very cold (it served as a warmer while sleeping) and during a failure (waveguide damage). The failure occurred when turning on the first millimeter channel of the station. After a while, I felt bad, I was afraid I would faint, I felt dizzy, the surroundings seemed to be undulating, I went outside the station, followed by the other two people. One of them said "I thought I was going to faint." I realized that there was a failure and there was electromagnetic radiation in the cabin. However, it was necessary to enter it to remove the high voltage from the transmitter of channel I. That’s when the suit came in handy, after putting it on and entering the station I felt normal. It turned out that the new magnetron had a crack at the waveguide output. Maybe someone dropped it during installation, because the damage did not occur during transport, because the magnetron, packed in a black canvas bag and foil, was suspended in the transport box on springs in a special yoke to which it was screwed with aluminum screws. And the distances between the plywood walls of the box and the magnetron were large, over 15 cm. The OP-2 coat was more useful because it was easy to put on and served as a warmer. Especially at a time when winter uniform regulations were not yet in force, and when on duty, you had to leave the staff house at night to climb the stairs to the 7-meter-high embankment. In order to make a planned or ordered radar observation.

At the end of the 1980s, microwave protective clothing was considered to be useless and the OM-1 suits and OM-2 coats used in the army were discontinued, without taking them away from their users, only the glasses had to be returned.

Whether microwave radiation was really harmful, I didn’t think about it while working at the station. The only health problems I noticed were bleeding gums when brushing teeth, frequent headaches, and suppuration of the eyes. I wasn’t particularly concerned about it then and I didn’t identify it with working on a radar detector. However, when, after 21 years of working at the station, I left for a position where there was no radiation, all these ailments disappeared over time. So I think they probably had something to do with microwaves.

The noise generated by various electromechanical and electrical devices (fans, encoders, antenna drive motors with reducers, waveguide pumps, transformers, transducers, rotary transformers, etc.) was also troublesome when working at the radar station. For example, at the MRŁ-1 station, the acoustic noise level in the cabin according to the instructions was 85 dB, but I think it became higher over time. Unfortunately, hearing protection was not provided. At stations where the transmitters and receivers as well as the antenna system were placed in a rotating cabin located on an artillery carriage, away from the apparatus with indicators and control system located on the car, this problem did not occur. It also did not occur at stations operating from portable indicators located at the airport or at the command post, connected to the station by cables or via the RL-30 radio link. However, the voltage stabilizers were very noisy there, especially on the indicators of the MRŁ-1 station. The second bothersome factor in the summer was the temperature, the increase of which was caused by the large number of electron tubes and other electrical components that heat up during operation.

A problem at some airport facilities (radio direction finder BRL, DRL, RSL, MRŁ) was dealing with physiological matters during duty. You had to go to the airport (RSL), in other facilities there were wooden free-standing toilets (slovojki) installed above the feces pit. Toilet paper was not provided, it was replaced by quartered pages of "Soldier of Freedom" or "Wiraży". At the MRŁ-1 station, after the port was commissioned for renovation and reconstruction, we lived in a steel body (kennel) after some defective communication device removed from the Lublin-51 car, and we dealt with physiological matters in the forest. Finally, after more than a year of duty in the "kennel", taking into account our requests, a dozen or so boards and square timbers as well as a box of nails were brought to the station. We had to do the rest ourselves. It was similar with the residential house intended to replace the tight metal body. Free bricks were obtained from the district office, but to obtain them, a two-story building in the forest had to be demolished. We got a KrAZ truck and a few soldiers to help us. We had to clean the demolition bricks and then build the house ourselves; we only got cement, sand and concrete slabs for the ceiling from the supply battalion.

Occupational health and safety when working with electrical equipment consisted mainly in periodic passing of a specialized qualification examination in the field of operation of electrical and power equipment with voltage up to 1 kV. After passing the exam, you received an appropriate certificate issued by the military fuel and energy inspection. The certificate was valid for 5 years. They were issued in three categories: E – operation, D – supervision, K – management. Mainly the basic category E was passed, category D, apart from knowledge from category E, required knowledge of legal acts. Initially, the staff traveled to designated examination centers (e.g. from Western Pomerania to OSSUL in Grudziądz), later examination boards came to the units in situations where a large number of staff were to take the exam. Then, those whose qualifications expired in a year or those who wanted to increase their qualification class also took the exam.

There were occupational health and safety and fire safety instructions at radar stations, radio stations and radio lines. In the initial period, knowledge of them had to be confirmed with a signature. Later, no one paid any attention to it. There was a part-time occupational health and safety inspector in the battalions (divisions), which means that in addition to his own official duties, he had additional occupational health and safety duties. He periodically checked the condition of electrical equipment by entering comments in the work book. These comments had to be deleted immediately. He did not control the communication and radar equipment and the power generating units that powered them, it was the responsibility of the station commanders. He paid attention to power tools, electronics, plugs, wall sockets (often torn out), grinder covers, kettles and electric stoves in companies, bunkers, workshops and airport staff houses. He requisitioned the so-called Immersion heaters for water made by soldiers from razor blades were buzzing. He checked whether occupational health and safety instructions were available in workplaces and workshops. Sample templates of occupational health and safety instructions were included in the "Information Bulletin on occupational health and safety" No. 1/1983. There were 33 instructions on health and safety at work in mechanical workshops, carpentry shops, operating cable lines, acetylene cylinders and even installing and repairing fluorescent lighting. Occupational health and safety at communication devices was described in the Communication Operator’s Manual, part XIV. In addition, the inspector received publications from the National Labor Inspectorate regarding occupational health and safety. For radar stations, radio stations and radio lines, as well as electric generating sets, their commanders were obliged to develop health and safety instructions themselves based on the equipment operation manual. They were approved by superiors. All in all, the instructions were a safeguard mainly for the command, because users often worked in their own way. By inflating the tires of trucks without protective cages because no one wanted to go get a cage, or by removing covers from saws or grinders because it was more convenient for them. The occupational health and safety inspector sent insulating rugs, gloves and dielectric rubber boots from radars and radios for verification. However, he was mainly occupied with writing post-accident reports for the battalion’s staff and soldiers, as well as civilian employees. Additionally, he had to participate as a student in periodic occupational health and safety training, ending with an exam. Of course, in the aviation regiment, each service had its own occupational health and safety inspector, so there was a part-time inspector in the flight command squadron, aviation engineering service and supply battalion. The only exception was the 4th Air Base, where there was only one emergency officer for the entire base.

Another part-time position was the unit’s metrologist. His duties included keeping records of all measuring instruments in the unit and checking their legality. This involved sending instruments for verification to various legalization units. In addition to portable electrical and electronic measuring instruments, scales in food service, pressure gauges in boiler rooms and kitchens, pressure vessels, gas generators, gas cylinders and meteorological instruments (anemometers, barometers, barographs and others) were subject to legalization or technical supervision. And there were also part-time fire inspectors. (legalization of fire extinguishers and control of fire protection) and part-time power engineers of the unit (legalization of gloves, galoshes, dielectric shoes, insulating bridges, insulating rods and tongs, rubber mats, voltage rod indicators) in subordinate energy substations. The latter two functions in the regiment were most often filled by personnel from the supply battalion, because it included the fire brigade and the airport maintenance company, which was responsible for the power stations. Of course, these functions were remunerated with a small amount of money depending on the number of people in the subunit, collected from a separate payroll. On average, it was approximately PLN 50 – 60 today. Most often, there were no people willing to take on an additional function, so they were usually appointed. I know of cases where one person held 2 or even 3 part-time positions.

Written by Marek Kaiper