Kraków 2017-12-19

Emergency abandonment of a military aircraft.

Part 1.

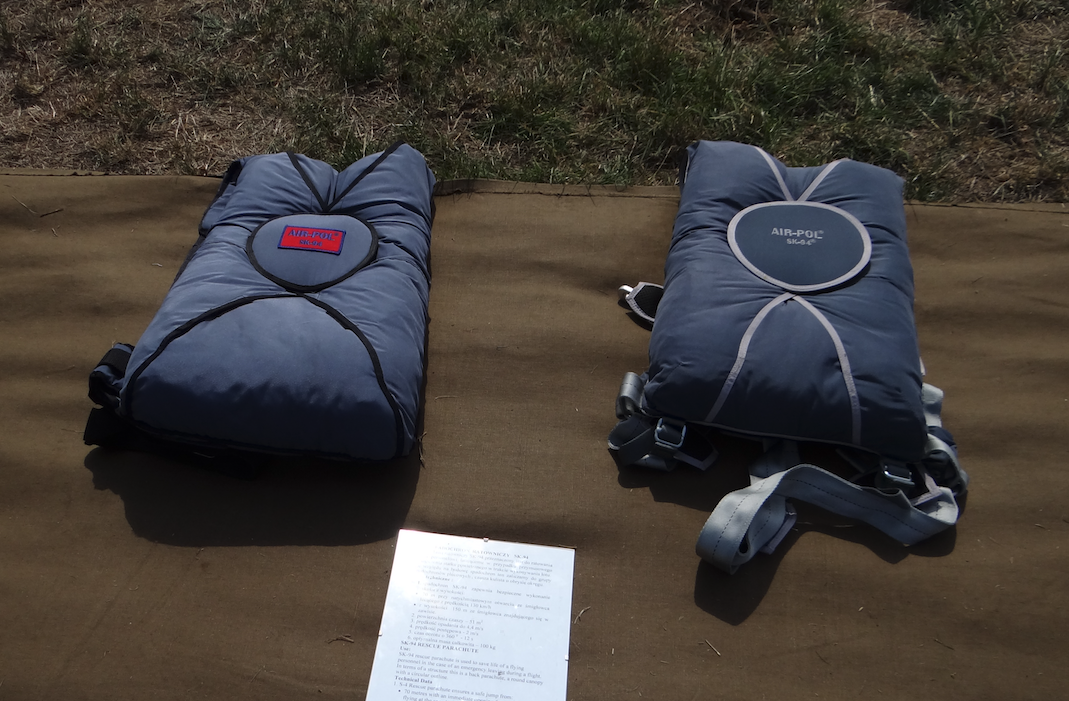

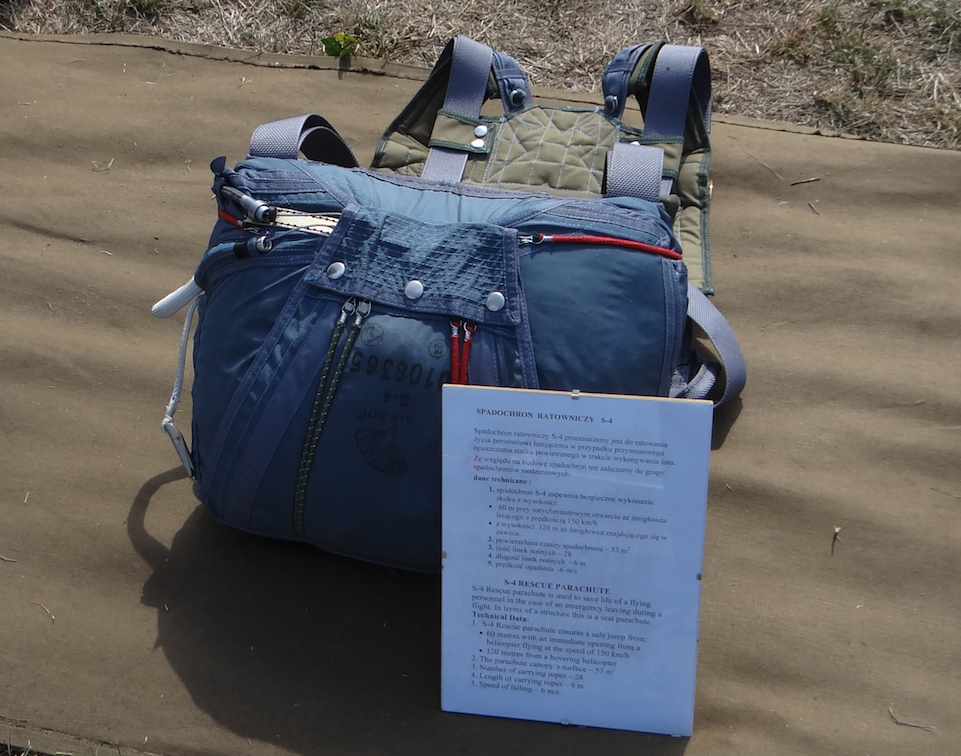

Rescue parachutes.

Failures of military aircraft cannot be completely eliminated. In addition, the plane can be seriously damaged during hostilities. It was like that at the dawn of aviation, it is so now and it will be so in the future. Therefore, the aviators who fly these aircraft must be perfectly trained so that they can solve the problem in emergency situations. And when all procedures have failed and the plane cannot be safely brought to the ground, they will be able to safely leave the aircraft and save their lives and health.

This saving health and life is inextricably linked with the possibility of using a parachute, which was already widely known in 1910. The problem is that even during the Great World War, parachuting was an insult, a shame, as young people say. After all, military pilots were "the best of the best." Life, however, made painful verifications.

Interestingly, the crews of parachute observation balloons used access commonly and it was not an affront but common sense. The hydrogen-filled balloon was an easy target for a fighter plane or even a sniper. And the parachute jump was easy and safe.

Until now, historians have argued about who first parachuted out of the plane. The first was rumored to be Grant Morton, who did the act in the US, California, in late 1911. The jumps of captain Albert Berry, who on March 1, 1912, performed this act in the US state of Missouri, are much better documented. The aviator used a Benoist Pusher two-seater training biplane for this task. Tony Jannus was the pilot. The aircraft was flying at an altitude of 1,500 ft (457 m). The parachute was placed in a metal container under the plane. The aviator had no harness. The 36 ft (11 m) diameter canopy had 24 lines and ended in a regular trapezoid. The aviator simply sat on the lower stick and jumped out of the plane with it. The canopy has been pulled out of the container. The aviator descended approximately 400 ft (152 m) before the parachute was fully filled. The experiment was successful.

In 1918, the US Army announced a competition for a rescue parachute. The proposed parachute should meet 11 requirements. In 1919, Leslie Irvin, a 24-year-old stuntman from California, demonstrated the first parachute. After the presentation, the experts were very pleased because the parachute could be opened far from the plane. Until now, parachutes were deployed when the pilot left the plane. When the plane was in a spin, it was impossible to use a parachute effectively in such a situation. Leslie Irvin has developed a pilot which, when it slips out of the cover, opens automatically and pulls out the main canopy. The parachute was adopted by the USAF and RAF. Leslie Irvin founded the company "Irvin Air Chutes Corporation".

Despite the relatively low price of the parachute and its advantages, pilots still did not like it. Therefore, in 1922, the Caterpillar Club was established at Irvin, which awarded a badge to all people whose lives were saved in an emergency by Irvin’s parachute.

In 1923 the Irvin parachute was already well known in Poland. Several pilots were available at each airbase. But they reluctantly reached for them. It was only in 1926 that Colonel Ludomił Rayski gave an order to take parachutes with him to the plane. At the same time, a larger batch of them was purchased. Talks on the purchase of a license have also been initiated.

Production started at Centralne Zakłady Balonowe in Legionowo. Lieutenant Stefan Nowicki became the manager of the new workshop. Since then, Legionowo has become a pioneering parachute sewing center in Poland. Preparations for the implementation of their production began in mid-1928. The parachutes were manufactured under a license purchased for PLN 500,000. This sum was returned within 3 years, and the cost of the parachute produced in Poland was three times lower than its foreign counterpart. The retail price hovered around PLN 1,440. The Polish parachutes of Irvin were called "Polish Irvin". They were also exported. Apart from sports parachutes, rescue parachutes with a diameter of 7.30 m were produced. They were produced in several versions, depending on the position on the aircraft. Seat type – for pilots, Back type – for balloon and airplane crews, Chest type – for observers, airplane shooters and balloon crews, Practice type – for training and sports. From the moment of serial production, parachuting has developed in Poland.

Written by Karol Placha Hetman